Introduction to Memoir with Tamara MC

I

Dr. Tamara MC: know we all Oh, you got now. Yeah. Okay, cool. Just tell me when you want me to begin I know you're waiting for a few more people

Elizabeth Santiago: started, because Tamara , Tamara has with their so we're part of the grub street community this is how we know each other. And so if you don't know grub street it is a creative writing center in Boston, but since the pandemic.

It became. You know, virtual as well. But anyway, at any rate, there's a conference this week. And I actually didn't keep that into take that into account when I scheduled this, but Tamara has to go off and do another workshop. So we're going to end at 655. But I'm going to turn it over to her so she can get started.

I just have to say I'm really excited because we did an intro to memoir session, um, I don't know, maybe six months ago. Um, and it was so fantastic. So I'm really, really excited that, uh, she came back . Um, and so I'm gonna turn it over to her to, to kick us off. Thank you.

Dr. Tamara MC: Great. Hi. Well, we have a cute little group here.

I like this. Four of us. Yeah. So I already met Joanne and Michelle. I'm Tamara and I'm Tamara MC. And, um, I have a slide deck that I made. That's kind of fun. So I'm going to put it up. So I'll, um, see, let me just, sorry, let me share my screen.

Alrighty. Can you all see? Okay, great. Um, so I decided that it's so hard, like I was like, how do I, I always like to teach different, but I was like, how do I teach memoir? Like I can come up with all the things that memoir is. And then I decided, well, why don't I come up with what memoir is not? And for some reason that felt easier at the moment, because I think it's, it's often easier to define something by knowing what it's not.

And when I say what memoir is not, It has to do with mostly published memoir. So if you want to publish your memoir and put it out into the world, then these are kind of good practices. If you're just writing for yourself, then maybe these won't exactly, I mean, you don't have to do all of these, but again, it's like good advice kind of in any sort of writing.

Um, can I ask both of you like what, like what are like, what's your experience with memoir? Since we're a small group, we can chat a little bit

or writing, writing and memoir. I'm

Joann Garrido: about 10 years ago I did take a memoir writing class. And I was the oddball in the group because everybody was writing about really painful memories and life experiences, and I was writing like silly travel anecdotes because I. It was just not what I wanted to do. So, but I mean, I think people enjoyed them.

It was, you know, at least I wasn't crying.

Dr. Tamara MC: That's

Joann Garrido: it. And I think I lost that file that I was like 10 years ago and I have no idea which computer they ended up on and. Yeah, that's bad. So hopefully I will find them somewhere.

Dr. Tamara MC: Yeah, that sounds really fun. How about you, Michelle?

Michelle Monti: I have the opposite experience, which is I had a painful experience as a kid.

And then my whole life I've been trying to write about it and have tried honestly, like multiple times. And finally, I'm at the place of like undoing all these shoulds. There's, you know, all the shoulds and then realizing it doesn't have to be painful. I don't have to relive it and go through pain to get there.

Um, so I'm shedding a lot of that and now I'm like ready. Instead of writing, because I have to do that. Like, I have to tell the story. Heart,

Dr. Tamara MC: Elizabeth.

Michelle Monti: Instead of writing because I have to, I'm gonna write because I want to. And I might not even directly tell the story. Maybe I'll just use it in other

Dr. Tamara MC: Ways to tell stories.

Yeah, that's great. I mean, I've, I've come sort of from the same background and I just have always felt so much weight on my shoulders. Like even from my ancestors, it's like, it's like it's all there. And so I've always felt so propelled to write and it's something that I still struggle with like all the time.

So I totally hear that and I did put Dear Lord and I added the E according to Lord, the wonderful artist who sings royals, who says that saying Lord without an E is like the E feminizes Lord instead of it being the masculine Lord. So I'm kind of a Lord fan. But, um, you know, this will be interesting because we don't really, there's just a So here we are, we're going to get lit, and if any of you know Mary Carr, she wrote Lit, the memoir, and also Liar's Club, and I highly suggest Mary Carr.

She is one of, kind of, um, the most well known memoir writers of our time, and one of the greatest teachers as well. So even on YouTube, finding any Any of her videos is great. So I was going to ask like, as a way to introduce ourselves, you could please introduce yourself with a show that you're watching right now on Netflix, HBO Max, or a podcast or a favorite food or dessert.

So whatever. Whatever you would like. However you would like to introduce yourself.

Joann Garrido: Um, although, um, well I just, I just, um, I just finished watching the third season of my brilliant friend on HBO. I read all the books. Oh. Um, and I, you know, Elena Ferrante is anonymous. Nobody knows her, but you can't help but think that, um, you know, these stories that she writes are so deeply personal and they're so, they're just so much of, like, growing up on rough streets of Naples.

Um. That I've just gotten I've just enjoyed it tremendously. Um, yeah, I've read all the books. So now I feel like I'm waiting because I started reading her books like last the end of last summer and then I caught up with the two previous seasons that were on HBO Max. So now I'm like, it'd probably be a year.

Until I get the next season. So I'm like, I know what happens with, I've read the books. I got my sister into them too. So she'll make comments and I'm like, I'm not saying anything. I don't want to spoil things for you, but I know what's going to happen with Elena.

Dr. Tamara MC: Yeah. Yeah. I'm so glad you mentioned that I have not watched that yet.

And I am like needing new, a new series to watch. So I'm excited. How about you, Michelle?

Michelle Monti: So, I'm this, like, non traditional rebel. I hate binge watching. And I will wait until, like, years pass, and then, okay, fine, I'll watch the thing. But, I have to go, like, anti your questions and tell you that I am a lifelong SNL addict.

Like, I record Saturday Night Live every week. Okay! Skip the commercials, and then you get 40 minutes of content. Instead of an hour and a half and that's like my favorite like dream thing would be like go write for them Even see a taping just like it's lifelong And it it I love comedy and I really like admire how they can actually tell truths with

Dr. Tamara MC: comedy So I think you can be more true in comedy, and I've been taking satire and comedy classes lately and through Second City.

Have you ever heard of them in Chicago? Yes. Yes. So they have online classes right now. So definitely, and there's other places too. So highly suggest that. And Elizabeth, I don't want to ignore you.

Elizabeth Santiago: Oh, it's okay. I, uh, yeah, I, I just started last night. I didn't finish it. Um, but documentary on Netflix about a contestant who knew too much.

Have you seen this about the price? I didn't see it yet. No, it's been hilarious. Like, I mean, I was just like, wow, I won't give anything away, but, uh, just, you know, what is it about? Well, it's um, it's about the show, The Price is Right, and this super fan, let's just call him that, who like memorized all the prices of every item on the show, and then got on the show.

And so I haven't gotten to the part like what happens, like I'm assuming. He knew too much. Like, you know, he, he probably got every price right. So, but I, I, uh, it's very funny. Like to me, like I, I just, the character cast of, I mean, they're real people and Bob Barker of course is like 98, but he's still, you know, he's still, they're just funny.

Um, so anyway, I recommend it. It's just been a nice thing.

Dr. Tamara MC: Yeah. That sounds good. Yeah. I never used to watch TV like anything and I'm single and I've been single for a while but now I'm also an empty nester and so like watching my little series is like my guilty wonderful pleasure in the evening. So I am like watching so many things, but if I'm so late in this but have any of you watched Outlander.

Like the five series. Oh my gosh. Like, cause it's fiction. It's based on the novels by like, so yes, it's crazy, but it's kind of this wonderful, but it's forever. And it's this wonderful love story.

Michelle Monti: So on comedy, Tamara, have you watched um, Schitt's Creek?

Dr. Tamara MC: I haven't watched Schitt's Creek, but I got to, right?

Do it. But is there something? Yeah, I gotta watch Schitt's Creek. I think the first, yeah, the first

Michelle Monti: few episodes are like slow, draggy, but then the writing

Dr. Tamara MC: is hysterical. Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. And I just started the new thing about Marilyn Monroe on Netflix, too. It's like the Oh, I wanna see that. Yeah. I saw it yesterday.

Elizabeth Santiago: It was so good. Yeah. It was very good.

Dr. Tamara MC: I just love all these things.

Elizabeth Santiago: That's good. Not a lot of us, right? Yeah. Yeah.

Michelle Monti: Good icebreaker. I like this question.

Dr. Tamara MC: Um, so let's see a little bit about me. Um, I grew up in a commune. When I was five, I grew up, both of my family members were born Jewish. My grandmother's a Holocaust my grandparents are Holocaust survivors from Lithuania.

And when I was. five, my Jewish father did the impossible crazy thing and he converted to Islam. So he became a Muslim and, um, his family basically disowned him and he followed a leader and joined a commune in Texas. And I grew up four months of the year with him. And then eight months of the year with my Jewish mother.

So I grew up simultaneously. Jewish and Muslim. And, um, I ended up learning Arabic and Persian and languages super young. And also my grandmother spoke Yiddish. And I, I was just exposed to language. I ended up going on to get a PhD in linguistics. I'm an applied linguist and I focus on the Middle East, like language, culture, and identity in the Middle East.

Um, but I always actually. I never wanted to be a writer. Like most people are like, I always wanted to be a writer. Like that was my dream. And I always knew that I had a story to tell and that I had to become a writer to tell my story. And so I kind of went about it in a different way on the commune where I grew up, we weren't allowed to read, we weren't allowed to watch TV.

And so I didn't actually have access to books. And so I think because of that, me not wanting to be a writer, it wasn't even like, Like, I couldn't even imagine what that would look like. And, um, but then after I graduated with my PhD I was in academia for a little while, and then my grandmother who was like my greatest mentor my Holocaust survivor died.

And within a few days, my ex husband asked for a divorce and I'd been married for 18 years and it was like terrible timing. And at that point she was in the hospital and I remember sitting there and I just started recording everything she was saying and everything she was doing. And I ended up before I know it, I had a 350 page memoir that I never even planned to write, and I didn't never even thought of myself as being a writer.

So that was 12 years ago. And since then, I have been on this search of like studying everything I can about writing I began, even though I wrote the memoir. Like had been writing poetry before that and so I applied to Columbia University for an MFA after my PhD and I got in in poetry and I started writing poetry and then people started reading my prose and were like, you need to be a nonfiction.

So I ended up switching to the not actually I was in both. I got into poetry and nonfiction. So I did both. And now I've just been a nonfiction writer. And I find that when I was writing poetry, it was really easy to kind of cover up what I think I needed to speak about. Like in poetry, you can be very mysterious.

And I feel like I was hiding in a lot of ways, but I couldn't really express, like people didn't really understand what I was saying because it was always like hidden. And poetry is like that. It kind of gives you that option. Like all different genres of writing have like kind of their. pros and their cons.

Um, so I have been writing now for the past, just exclusively pretty much nonfiction for the past five or six years. And I was in Grub Street, as Elizabeth mentioned, they have a memoir incubator, which is a year long program that you apply for. And then you're there for the year and you're writing your memoir.

And so I spent a year and I wrote this memoir that came out to be 350, 000 words, which is the equivalent of like for novels, you know, basically, or for memoirs. And after that, I left there and it's like, All that weight that we were kind of talking about, Michelle, it's like it all came out. And for the first time I felt free.

So I didn't at the end have, I, I don't, I didn't have something that's publishable, but I was able to get out my story. And I think that that is the first step in writing is getting out the story, like having it on paper because before it's on paper. It's just in our heads. And it's just like, like, I just know my head is just get so cluttered with all these stories.

So, so in terms of just thinking about getting it out, however it wants to come out, even if it's in making videos, like I've made videos for so like, I've had so many different ways of like my creative outlets. But then after I left, I was like, I'm going to put my memoir in a virtual drawer and I have and I've just been taking classes, but I've been taking screenwriting classes and novel writing classes and journalism classes and comedy classes and romance and society.

Fence, like anything I can just to really learn the skills of writing. But memoir is the love of my life. I love writing about the self, I love all autobiographical writing. And so that's kind of what I personally love to do. So I'm going to, um, if you have any questions, I can answer that now about me.

Otherwise I shall go on to the slides show.

Michelle Monti: I think I have a quick question. Sure. Are you financially sustaining yourself as a writer?

Dr. Tamara MC: I am not financially sustaining myself as a writer. You have side gigs.

Michelle Monti: This is your side gig, so.

Dr. Tamara MC: Um, I made the decision that for five years I was going to do nothing else but write like a maniac.

And um, in my divorce decree, I had a little bit of money saved up for my retirement that I got from my ex, and that's what I'm using, which I should never do. I should be waiting until I'm 65. But I was like, who knows if I'm even gonna live that long. I was like, and I have simplified my life. I live in a trailer in Arizona and my rent is 400 a month and I have just completely made my life so that I can write and that's my priority.

So I guess it's just, and I'm in a position now that, like I said, I'm an empty nester and I can make these decisions. So thanks for asking. I'm going to share my screen again. Whoops. When I do that, I lose you all.

Elizabeth Santiago: Can you see us on the side?

Dr. Tamara MC: Yeah, yeah, I know. I got you now. Okay.

I just put in that little thing, but I already introduced myself. And that is obviously not me, but I like her. She's cute. Yeah. So, so just a few reminders before we start, which I'm sure we all know that everything we share is personal, but I know that we are making a recording. So actually that does change a little bit.

So do keep that in mind. Um, and I love that we have our cameras on. I just think it's really important when we're talking about ourselves that like we are visible and we all know that we're safe in this setting and. We're just again such a small group but mute buttons and this will be kind of a cutesy little presentation, and our last little.

So this is what I was going to do I was going to go over our 10 little thingamajigs that we're going to talk about and then just have a little bit of writing time, and then optional sharing if you want to and then any questions.

So here we go are we're going to start the countdown begins. So memoirs are not two truths and one lie. Have any of you played this game. Okay, Joanne. It's a game I often play with my. Sorry you haven't know. Yeah, so it's a game I often play like I teach a lot of ESL classes and I love them to like practice on like you're supposed to like say three things about yourself.

And then people are supposed to guess what is the lie. Okay, so like there's two truths and then one lie. And so I put this in here because memoirs are true. They, there, there isn't one lie in there. It isn't two thirds the truth and kind of one third false. This is not fiction writing and, um, it is based on the truth.

And when we speak about truth, I really like to think about emotional truth. And what is the emotional truth of the piece? Because again, Memories are actually memories of memory. So memories still are like not to be trusted in many ways because you can ask two siblings the same thing, and they will both have a different story about what happened and how it happened.

But again, a memoir is our story. So we just have to be truthful to our story. That doesn't mean that we don't do research and kind of like make sure that our story kind of the facts actually support our story that that's really important in memoir writing and even listening to different people's stories.

And have any of you read Educated by Tara Westover? A memoir. Okay, highly highly recommend it again one of those memoirs you have to read. And Tara actually was an academic as well had her PhD kind of had a similar story to me, and kind of started out in like this comm well not a commune but she started off without like being homeschooled and then went on to go to I think it's Harvard Harvard for her education got a PhD, and kind of, um, exceeded her circumstances that she began with.

And in her, um, in her memoir, she actually puts little footnotes about different stories that let's say her brother thought happened a certain way. So it was really interesting how she actually added footnotes, but you don't have to do that in memoir. That was just a way that she kind of went about it.

Um, but looking at like the emotional truth of the piece. Like maybe we don't know whether or not your sister was wearing a blue dress or a red dress that day. That is not important unless the red dress is important to the story. So to just think about what details are important and to keep to that truth.

I put this in, memoirs are not yo mama jokes. And this can kind of, this is um, This is something that I've actually struggled with in my memoir in terms of I have been so when your mama jokes, which I'm not talking about it actually being jokes, but it's always about the mother, the story is always about the mother right, your mother did this, but memoirs are about us.

So we are the main characters in the memoir, and I, and like all of these kind of little tips that I'm giving you are from like mistakes I've been making for years and years, most of these. And I think this is kind of something that I've always, I've written my memoir so many times at this point, and in almost every version it's actually my grandmother's story.

And no matter how many times people tell me that, no, we don't want to know about your grandmother, we want to know about you, I'm still like fighting, like, no, I want to tell my grandmother's story. But in all of the feedback I've received, it's like, I am the sun and all of the characters are the planets that revolve around me.

And so it's so important that in our memoirs, we're in the center and we are there. And I think that that's really hard because oftentimes like Probably a novel writing. Like you can have multiple points of view, like, you know, you can have like a cast of characters and there are characters in memoir, but again, everything has to be filtered through the lens of the main character who is the memoir writer.

And that seems kind of easy, but it's kind of tricky. I think, I mean, I just know for me, like I've kind of how I grew up. I love telling stories and. Not like exposing things, but I just love my family stories. And I love speaking about my family, but so often I'm not even in those stories. So that's like parts that I have to like, be really careful of when I write memoir.

Memoirs are not everything, but the kitchen sink. So I'm a vegetarian. So let's say that I wanted to make a recipe for potato and pea curry. So I would have potatoes and peas and all of my curry spices and onions and all of that, but I would not bring the strawberries out of the fridge. I would not be putting chocolate in this recipe.

I would only be using what I need for this actual recipe. So our memoirs are a recipe that are actually a specific story that we are telling. They are not our entire lives, that is an autobiography. So that would be kind of birth to death, and generally autobiographies are really written by autories.

writers later after somebody passes away of somebody famous. So we will generally be writing memoirs, which means that we're going to be taking a small part of our lives and writing about that. We're not going to be writing about everything. And actually, memoirs that have a very, like, time constraint are really good memoirs.

I don't know if any of you have read Cheryl, Cheryl Strayed's Wild, um, another highly recommended memoir. Um, in her memoir, she's writing about the time that she hiked the Pacific Crest Trail. Now, she goes into backstory, but all of it has to do with what's happening as she's walking this trail. So, she isn't speaking about her entire life.

Could you imagine, like, if we all spoke about our entire lives? Like, we would never finish, and nobody would be interested, so. Any questions before I go on about Any of these so far. I just have a quick

Elizabeth Santiago: question. If you're like, I always had this concept of writing a story about my family in each person had a different chapter.

It's very anti memoir in some ways but like I wonder if it maybe falls into the category of essays, like personal essays or. It just seems like I can't quite fit it into a

Dr. Tamara MC: construct. Yeah, you know there are non traditional memoirs, like it's really opened up memoirs used to have a pretty traditional feel to them.

And I feel that now with so many different voices and so. You know, it's just opened up so I could definitely see that as being a possibility. Um,

yeah, I mean it's just, again, it's it doesn't follow the traditional form, but it's cool. As long as that's okay like I was just sort

Elizabeth Santiago: of Processing

Dr. Tamara MC: that. And I've heard like, I mean, generally you want to know kind of what you're writing, and then when you send it out you want to know. But I've also heard other times people just kind of explain themselves like when you're trying to get a literary agent, this is what I've done.

And then oftentimes the literary agent will say, oh, this is a memoir and essays, or, oh, this is like essays. And so sometimes we don't have to worry about that, you know, so you can also keep that in mind. I have a

Michelle Monti: similar question. Um, writing about family, I wrote something about an experience, you know, and it's not very flattering about a family member, so I do not handle that because that means I would either censor my whole book or ask their permission and to sort of explain it's just my experience.

It doesn't mean I don't love you,

Dr. Tamara MC: you know. Yeah, so maybe that'll kind of follow into this slide. So I'm going to kind of talk about that now. So memoirs are not Freddy Krueger and Nightmare on Elm Street. So what does that mean? Freddy Krueger was vengeful, and he was vindictive, right? So we do not write memoirs.

to take a vengeance on anybody. We are telling our own stories and our truthful stories. Now, do they, do these stories have consequences? Yes, like, like they can have consequences. And so I think in the beginning, whenever we're writing, we need to take away all family members. Like we need to be in a room with ourselves and tell our stories, like that's number one, like the questions of how are they going to feel, how is this person going to feel, those aren't even questions that need to come in at that point.

You need to get your story. So do not censor yourself at all at that point. And as you write, you're going to have so many drafts. And like maybe in the and again like this Freddy Krueger nightmare on Elm Street. In your first, second, third draft, you may be vengeful, you may be angry, you may be hateful, but as you keep going through drafts you're going to get to a point.

Where you kind of lose that that edge is gone. And so you can expect that in the first drafts and your first drafts you just have to do whatever you have to do you got to get it all out, and nobody has to see that you can bring it into a workshop, but, um, But oftentimes there are legal teams that will go back and kind of look at, you know, if you're going to go like with a publisher that will actually look at that or if you're going to have essays published there is there are legal teams to kind of address that.

And then often memoirist. When they're all done with their story, they allow the person that they wrote about to read it and they let them know that I am not saying that I'm gonna change anything, but I'm allowing you to read it. And if you do have recommendations or if there is something that you need me to take out, I'm willing to listen, but in the end, this is my story and I'm gonna make that decision.

So you always have the right, but it's also. if that's a practice you want to do. Like, for instance, Mary Carr, from what I remember from listening to her, she does send out her pieces to be read. And usually this is at the very end, like when they're almost ready for publication. So not in our beginning drafts.

So, so yeah, so, so definitely don't, don't worry about that now. And also in memoir, Your characters aren't going to go by their first names. You can change their care. Like, like you can change traits in that way. That does not make it fiction in any way. That's just protecting identities. Sometimes we can't protect identities because we're talking about our mother, for instance.

So, you know, it gets a little bit tricky, but yes. And if I didn't answer that, I can go into that more.

So here's my other one. Memoirs are not there will be sad songs by Billy Ocean. And um, I think like I'm saying two things with this. Memoirs are not sappy. Like you don't want a sentimental memoir, if you want it to be published. So, um, if you're writing for your family and you want to leave a legacy for your grandchildren or your kids, absolutely be as sappy as you want.

But, um, sentimentalism and kind of writing things in a way that like, it's just like too sweet, like honey, like, like that's, that's not a memoir, you know, you want it to have. You want to have a balance of emotions. You don't just want to kind of it to be PR as well. Like everything, you know, was wonderful and this, everything like it, you know, which I don't think most memoirs are, but also the opposite of that too.

Like you don't want everything as horrible too, but, but really like, like having that balance, I think is important, but oftentimes you can read people's life stories and nostalgia takes over and nostalgia isn't really. It's fun to read, like, by the spoonful, but it's not really fun to, like, read a whole book about, so.

And when I speak about memoir, that's maybe something I didn't say, I'm talking about book length. So usually essays are shorter pieces, like, that can be, you know, I don't know, 800 to 1500 words, like 10 pages or so, 6 to 12 pages, something like that. But when I'm speaking about memoir, are those questions for me?

I don't know. I don't have on my chat thing. Oh, sorry, I doubt it. Okay. I just heard something coming in. Um, um, yeah, so, um, so when I'm speaking about memoir I'm speaking about like an 80, 000 word book that's generally what a memoir is which is about 350 double spaced pages. That's typically 80 between 90, 000.

Usually anything over 100 is just way too long.

And memoirs are not the United Nations vision statement. So, this is not like a peace treaty. You're not writing, like, there has to be conflict like in novel writing. Like, there has to be page, like, it's a page turner. Memoirs are very, very simple. similar to novels. And I believe that they should read like them for a good memoir.

That's my personal choice. Um, so, so there has to be conflict. Why is each scene in there? Again, we have to question why are we writing about this? What is the change? What is the conflict? How does the scene begin? How does it end? And And they, and basically it should be very different, like how the scene ends when it's over, the character should have a change, if it's an emotional change, if it's a physical change, but something has to move the story forward, because it is forward moving.

There's only a certain amount of pages and you want people to start in the beginning and end it so what's going to keep them there. It's not going to be a memoir that just has a whole bunch of stories, but doesn't have conflict.

Okay, are all of you familiar with Rikki Lake? I'm an 80s girl, so she was all over the airwaves. I don't know if any of you've seen Hairspray, but, um, but her hair does not move in Hairspray. So, um, so kind of going back to like the change and the transformation. In a memoir, your main character, who is you, is going to have a change and a transformation.

They're going to begin in a certain way, and they're going to end in a certain way. There's going to be a beginning, a middle, and an end. So how is this character going to change? They are not going to be Rikki Lake's hair, where it just stays still with the aquanet. Any questions before I move on?

Elizabeth Santiago: No, just love the aquanet reference.

That's all.

Dr. Tamara MC: Okay, memoirs are not Casper the Friendly Ghost, or any ghost. And as wide I say, is ghosts are made of what? vapor, like they're formless, right? They're just kind of out there. They can kind of like move and it's like, you don't really know how big they are. Casper does have a form, but let's just say a real ghost, assuming we believe in ghosts.

Um, so, so memoirs have structure and form, and I think that that's super important. And in my first drafts, it didn't have a structure in a form I was just writing. But as you get into your further drafts, you're going to have to decide is this like the three act play structure is it a non traditional structure kind of like Elizabeth was talking about like, like different, different people story from different perspectives, but kind of deciding on your structure later on, you don't have to decide in the beginning structure can often come.

Like on your second or third draft so it doesn't have to come initially, but to think about that that there is a container and what is that container,

and they are not one and done son and I don't mean to be gendered here by using sun but I had to. So I can be human. But yeah, um, there are so many drafts. In a memoir, and I'm not sure if any of you are familiar with, um, Allison K Williams, she recently wrote a book called seven drafts, and she has a method, about a seven draft method, Matt Bell just came out with a book, well actually it's, he didn't just come out with it, but he recently, um, Um, his newest version just came out and his is about three drafts.

And so everybody can kind of say how many drafts, but I think like Allison said that she said seven drafts because she didn't want to scare somebody by saying like 40 drafts, or, you know, like, like there's gonna be so many drafts. And I think just to take the pressure off and not to worry and to know that everything can be fixed and it's going to take time.

And like I said, I have been actively working on writing for 12 years. I mean, and you know, I heard in the beginning it takes 10 years of like really honing your craft of writing before, and I kind of feel that like in my 11th year, I felt like, wow, I kind of actually know what I'm finally doing. You know, so it's not like it's not going to be one year.

It's not going to be two. I mean, maybe it is like, I don't understand. Like I've read stories of people starting their memoirs or their novels during the pandemic and they're already published. I'm like, how did that happen? Like, who are these pandemic novelists? I don't even understand. Um, yeah, if they have a trick, I don't know, but, but I honestly.

Maybe they have writers that have helped them, maybe they've really been working on it for 10 years, like, like, who knows, but yeah, I wouldn't, I would say that that is truly the exception.

And memoirs are not easy breezy beautiful cover girl going back to again the 80s cover girl no longer even has that is their cute little slogan. But, but yeah, this is not easy when you sign up to write a memoir. It is excruciating and if anybody tells you differently, I don't think that they're telling the truth.

Um, like, I hear people and they're like writing should be joyful and it should be, and yeah, but I think that writing about. the tough things in your life and memoirs are generally about our traumas. That is not easy and it's like every day or as many days a week as we choose to write, we have to bring that up and like come face to face with it.

So that's not going to be easy, but it's like, but there, but there's this joy in showing up and like telling this story and like. Having the opportunity to share it. And so, so I think joy in that way. And for me, I don't have a choice. Like, I feel like writing has chosen me. Like I, I have been writing, like, even when I was in academia for so many years.

But I mean, Pretty much for the past 12 years, I get up every single morning. This is not for everybody. I am like hardcore person, but I get up every morning and like start writing at five or six and I write seven days a week, pretty much four to five hours a day. I mean, it's just, it's my practice, but it's also like my savior.

It's like writing is my best friend. It is like. I can't imagine my life without writing. So, so, so, so those are the reasons that I write. Um, and let's see, I think that that those are the 10 little tips that I have, and I am going to stop sharing my screen for a minute.

Oops.

Okay. There we go. There we go. Perfect. Good timing. Um, any questions about anything that I just went over?

It was very quick. Oh, go ahead, Michelle.

Michelle Monti: Oh, thanks. Um, echoing what Elizabeth asked about, I've been hearing from people that memoirs are like, totally, you can do whatever now, you can have a poem on a page, you can draw a picture, no holds barred formats, right? I don't know if you have any opinions on

Dr. Tamara MC: that.

Well, first of all, with self publishing, you really truly can do whatever you want. If you want to be published with a traditional publisher, then there are going to be a lot of rules. And, um, it's still pretty much, you know, it's, I mean, it's still pretty much traditional. There, there, you know, it's a little bit more open, but probably not as much, but there are definitely exceptions to the rule.

So it depends on, on, on what direction you want to go with it. Right.

Anything else? If not, I'm going to go into our little writing exercise. If you have a little notebook available or a computer or whatever you have.

Elizabeth Santiago: I see that Joanne. Oh yeah, and Michelle. Yay.

Dr. Tamara MC: So I'm going to borrow this from Melissa Phibos, who again is one of my favorite writers and just came out. She's um, She's the author of girlhood and also just came out with another book on on craft and, um, she, I was just in a workshop with her, but she actually has this exercise and it's a little bit different.

I'm going to kind of revamp it a little bit, but she asked people to write five sentences. I'm probably not going to say this exactly right, but it's a sex, I forgot, but it's about their sex life because it's about sex or something. So it's like these five sentences. So we're not going to be writing about sex.

We're going to be writing instead a five sentence memoir. And so I want you to think about five sentences, not using a thousand semicolons. And I'm going to keep an eye on that. Now I'm not going to look at anything, but I want you to take a few minutes right now to just think about five sentences of your memoir.

If you had to choose five sentences and just let them come out just just let your subconscious play for a little bit.

You do you think you have five. Okay, cool. Now is what I want you to do is I want you to look at those five sentences. Now I want you to write three sentences from those five sentences and you can't reuse the sentences. So you've got to consolidate even more. So bring those five sentences down to three sentences.

So taking your five sentence memoir and turning it into a three sentence memoir.

Joann Garrido: So we're choosing from the five that we wrote and selecting

Dr. Tamara MC: three. You're going to take three ideas from that and write three brand new sentences. Gotcha.

Okay.

After you have your three sentences, we're going to move on. Gets tougher and tougher. Right, so I'm not going to make this easy.

You got it now out of those three sentences, I want you to write one sentence, a completely new sentence. What is your memoir?

You can turn off your mutes whenever you're done.

Michelle Monti: Like mic drop.

Elizabeth Santiago: I felt

Dr. Tamara MC: it. It's a girl! I believe I got it. Wow. I'm proud of y'all. That's great. Um, so I thought that we could do some sharing and so we can share, you can all make a choice of how you want to share. One, you could read your five sentences and then read your one sentence, or you could just read your one sentence, or you can talk about the process.

So, and I would like to hear both, like if you want to read five down to one and then talk about the process, that would be wonderful. But maybe we can each first read our sentences and then talk about the process afterwards so we can kind of put all the voices into the room. And if somebody would like to start, please just go popcorn style.

Michelle Monti: I'll do five in one. Great. Okay. Um, I'm a child from a middle class family who grew up in New England. I've always been a theater lover. You could say I'm a serial expressionist. Some descriptors include a mom, a fighter, and a survivor. I'm finally embracing self love in my 50s. I just want to do good on the planet.

And the one, I am a person who uses all forms of expression to contribute positivity to our world.

Dr. Tamara MC: Wow. So do you think, so we'll think about that. So this can kind of be a theme, right? That kind of all the stories that support this sentence are included in our memoir. So like you think about, this is what I want to write about.

What stories support this sentence? And you can change this a thousand times, but it's kind of a way to hone in and decide what am I writing about? What stories am I telling? What stories am I leaving out?

Michelle Monti: I totally get it. I have ideas for what that would be.

Dr. Tamara MC: Nice. Joanne, did you want to share anything?

Elizabeth Santiago: Sure. Um,

Joann Garrido: I'll read my three and then my Okay, great. Okay. Um, my immigrant parents installed an interest in travel and other world cultures in me. I haven't been that very career minded and interested in upward growth in the workplace. I feel a bit of pressure now at my age to do more exciting things. So my memoir is how a bit late in life I'm using my past experiences to build some life skills and new experiences.

Dr. Tamara MC: That's great. And I hope like I realized that maybe what I spoke about didn't have a lot to do with humor. So I hope that maybe you were able to get. a little bit out of it. And I mean, even like your travel writing, like that's a whole genre too, like travel memoirs. I mean, they're just amazing. So, um, so yeah, definitely.

So you can think about supporting stories that support that. Can you think of some stories or scenes? Like you actually want to think of specific scenes that are like, that's going to bring the audience in to be able to understand without telling them. I saw you writing. Do you want to go? Elizabeth? Yeah, no,

Elizabeth Santiago: someone joined the waiting room, someone who registered, and I'm, I was typing, let her know, we're close to the end now, uh, but I will finish that momentarily.

Okay, I'll do five in one, um, okay, so, uh, I started writing, which I was surprised, but we'll talk about the process, but, you

Dr. Tamara MC: know, what could have happened just real quick, I wonder with the time difference, sometimes, I'm thinking, the whole network was huge.

Elizabeth Santiago: Yeah, I feel I feel bad. Um, I thought one way. Okay.

They said I wasn't going to mount too much. But after dropping out of high school, now referred to as push out, I pushed myself back in and earned a high school equivalency diploma. I carried a lot of shame around failing for a long time. But I realized I didn't fail. I saved myself by choosing a different path.

Now after earning a PhD, I know I've chosen the right path. Okay. And so my one sentence is sometimes you have to save yourself, even if no one understands it.

Dr. Tamara MC: Wow. See, now that is like a perfect memoir theme, isn't that?

Elizabeth Santiago: I'm getting the hang of this.

Dr. Tamara MC: I want to read that memoir. Yeah, definitely. So, so how, how did that experience feel?

If anybody would like to share, how was it? Easy, difficult? I

Michelle Monti: will share what I thought was interesting is when you first said write the five sentences The first thing were like more like nouns and I just like wrote what was like you said let it come out So I just was like popping out phrases about myself and then I had to go back in and put make them sentences Because it was like what key words were popping out in my head.

I guess that's just my process. Well, that's fine words and then Then the other thing is that it sounded so scary to have to cut it down, but it wasn't as scary as it Okay,

Dr. Tamara MC: good. And that's the whole point is to realize that it is scary, but once you just got to do it, you got to chop, chop, chop.

Joann Garrido: I thought it would be difficult to like, you know, round your life up into five sentences, but I did find that what I wrote. Really wrote a little story about me and it's what I picked and then I was able to even you know and to cut it down to three I'm like I'm going to go with the three that I feel are are most important to who I am now.

So, it was easier than I thought because you always get that panic you're like oh my god I have to write it's gonna be like five minutes

Dr. Tamara MC: now. Yeah, I'm Melissa feebos I think. Um, when Melissa does this exercise, she actually has her, if we had more time, she says, write five sentences, write again, five more, five more.

And she keeps doing it. And you can't write the same five sentences, but you keep distilling, distilling, distilling, right? And that's kind of what we're trying to do is to distill our story down so that we can actually have others understand our story. Because that's, I mean, If our goal is for our story to be in the world, then our goal is to communicate and the way to do that is to really distill down what we're trying to say.

So, I hope that something of what I said you can bring into your future writing life and I wish you all the best in writing and if you have any questions or anything. Actually, I'll just, um, hold on a sec. I'll just Lastly, real quick, I'm going to share my, my info here in case you would like to, um, in case you'd like to absolutely reach me in any way.

And you can take a screenshot or whatever.

Michelle Monti: Good idea.

Elizabeth Santiago: I might already do that. Say that again? I have to follow you on Twitter now, but I might

Dr. Tamara MC: already do that. Oh, I'm not, I'm just learning how to use Twitter. I'm terrible at Twitter, but it's where writers are, so. Yes. It's important. So yeah, well, thank you so much.

And if you have one last question, I have like another minute or. No, I just love

Elizabeth Santiago: everything in your background. Oh, sorry. Yeah, no, and that too. Yes.

Dr. Tamara MC: Yeah, this is my little, um, I'm, I've like been an artist my whole life and I collect and I'm like, I have, I just collect things from all over. That's my grandmother back in the back.

That's my grandmother, Bobby Mina, my Holocaust survivor grandmother. So, um, yeah, and I'm a huge Lady Gaga fan. And I did some of my dissertation, um, The meaning of gaga, like a crazy wild gaga. Like when I think about God, I love pop culture. So anyways, well, thank you so much. Thank you, Elizabeth, for having me.

No,

Elizabeth Santiago: thank you for your energy and putting together a wonderful presentation. It was great as always. Um, so thank you. And just to let Joanne and Michelle know, there is another event in May on self publishing if you're interested. So, um, take a look at the site. But I'm going to send out a note about that recording.

Michelle Monti: I appreciate both of you so much. I appreciate you. Tamara. It's so nice to meet

Dr. Tamara MC: you. Yeah. So nice to meet you too.

Michelle Monti: And I love what you're doing with this initiative to give this to us for free and bring to Tamara from. With us is amazing.

Elizabeth Santiago: Thank you. You're welcome. Yeah, we'll do more. There's definitely more to come.

I want to go to that

Michelle Monti: trailer. I want to be there right now.

Dr. Tamara MC: In my trailer? Oh, it's the cutest little thing. I do. I call it, um, it's like, it's called my Barbie doll house. I love Barbie. So there are a lot of

Elizabeth Santiago: pink.

Dr. Tamara MC: The whole outside is pink. Oh my God. And it has flamingos and it has like the turquoise pictures

Elizabeth Santiago: of it.

It's amazing. I thought of you, Joanne. I was like, Joanne would love this

Dr. Tamara MC: road trip. I'll come get you. Yeah. And I have, I also have an ambulance that I converted into a trailer and and she's like adorable. And her name is Glambulance. Oh, you

Michelle Monti: have to watch. It's Creek. You're going to get so many ideas.

Dr. Tamara MC: Oh, good.

I'll have a motel. Yay. Now I have new things to watch. Awesome. Thanks all. Bye bye. Have a good

Elizabeth Santiago: night. Thank you all. Bye bye.

So just to give you a little bit of history, so I’m a trauma informed writing coach, and this is a trauma informed writing group where all of the writers are working on the tough stuff. And we’re looking at how do you navigate that in a way that allows you to thrive rather than just survive and be constantly triggered by your work.

As a part of this, we’ve been studying various essays, including essays on Dorothy Parker’s Ashes, and your essay, which we absolutely love. And so we’re so excited for you to be here, and I’m just gonna, you know, read from your bio because I really want us all to take in all of the things that you’ve done and the hard work.

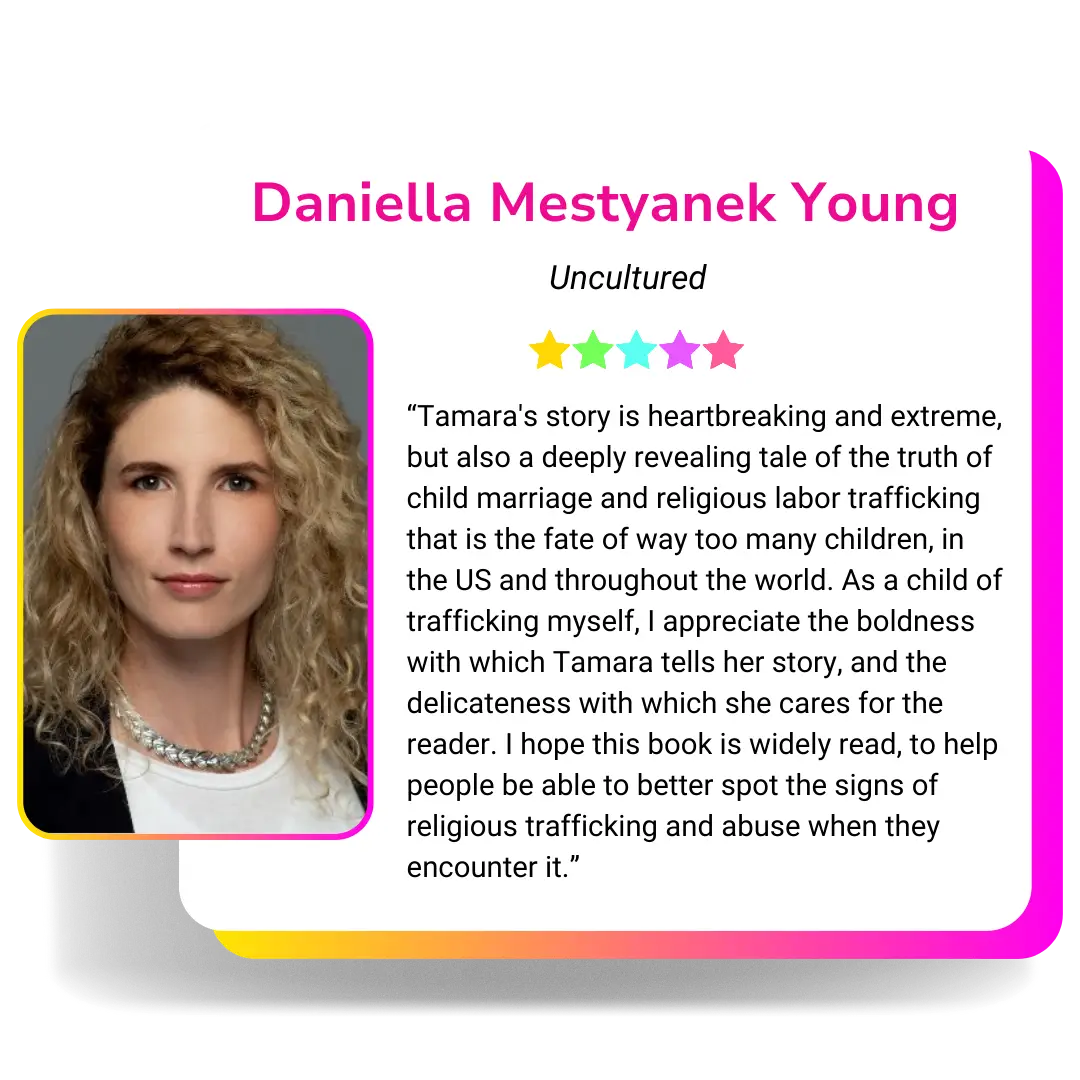

that you have before we talk about the answers to your questions and then you know, really the praise that we have for your essay. So Dr. Tamara Emcee is a freedom activist for girls and women worldwide. She is a social scientist and linguist who explores how language is used to manipulate vulnerable populations as a cult child marriage, polygamy, and modern day slavery survivor advocate.

Themes in her work explore coercive control, intergenerational trauma, religion, spirituality, and mothering. She researches languages, culture, and identity in the Middle East and beyond, specifically her hybrid identity of growing up simultaneously Jewish and Muslim. Although she was born to Holocaust survivors survivor Reggie G’s and feels without home.

She claims Lithuania and Belarus as her homelands. She’s also traveled to 77 countries and counting. and makes the world her home. In America, she has roots in Arizona, Texas, and New York City. She is an empty nesting mama to two sons and a grandmama to two pups, a Boston Terrier, and an Australian Shepherd.

She is a lifelong vegetarian and lover of all sentient beings, and in addition to Tamara’s essay in Dorothy Parker’s Ashes, she’s been published in Salon, The Independent, Bomb, The Strategist, Oldster, Hippocampus, Miss Magazine, and Motherwell, and she also appears on the following podcasts, Method and Madness, again for the first time, and Emancipation Nation.

She’s working on a memoir, Child Bride, about her marriage at age 12. So, so many things that you have done and so many accomplishments.

Dr. Tamara MC: Thank you so much. Thank you for having me here.

Yeah, well, I’m sorry I interrupted you. Oh,

Dr. Tamara MC: no, go ahead.

Well, I’m just grateful that you have chosen to be with us today so that we can talk about your essay.

So some of the things that really stood out to me were, was the visceral nature of this piece. There are so many details that take me into this moment physically, the Drakkar Nawar behind the ear, the sweat smearing across the narrator’s cheek all of those things. And when you couple that with like this great dissociative moment with the unicorn, it’s, it’s like you take us there and yet you also hold us in that space and help us make sense of it.

And I can say personally, I was connecting. I had this heart connection to your piece because I also had a boy who was like that in, in my own life. So there was like this feeling of connection with you just from reading your essay.

Dr. Tamara MC: Thank you. Yes, I think sadly so many girls have had a similar experience.

during their school years. So maybe in that way, people can connect with the essay because maybe they had this person in their life.

Yeah. I definitely think you’re speaking to a universal experience of unwanted attention and of what do you do with that, especially when, you know, there’s some layer of trauma around your life and how do you Navigate the mental acrobatics that we do in order to be liked, right?

Because that’s what we’re often socialized to do.

Dr. Tamara MC: Yes, and I think going back to like something you originally said was about disassociation. And I have found it a real struggle to write about that in, to actually write about disassociation. Like, how do we write that because we’re not even in our bodies at that time.

Yes. So how do we then come into our bodies as we’re writing and then be able to express that? So that’s something that I really struggle with. So I’ve worked with it a lot in my writing and a way for me, like in my memoir that I’m writing, I always, when I disassociate, I end up on my pink unicorn. So I can use that as a way to kind of show the readers this is what’s happening.

So without saying what’s happening. So I think that that may be a good way to show disassociation because it’s so hard to describe. But is there a place that we go when that’s happening? And to describe that place that we’re going. That really doesn’t exist, but it exists only at that moment.

Yeah, and I thought that was one of the things you did really, really well.

Like, you know, I knew exactly what was happening, I think we all did as readers, and yet you weren’t like, reader, here’s a little sign as to what’s going to happen next. And because there was this great moment of dissociation, You allowed us to fill in the blanks around what happened without having to, as the writer, you know, relive the whole experience, at least on the page, you know, what we had, what we experienced when we’re actually writing can be totally different than the words we see.

But on the page, it’s not there which means we as writers, readers are not also having to absorb all that as well. And there’s certainly times and places where that, that needs to be there, you know, it, but I think that was one of the things you navigated really nicely in this essay.

Dr. Tamara MC: Yes, and that’s I think also the second part of it that I struggle with in writing is how many details to give and how many details to leave out, especially when it comes to rape and sexual assault.

And I think like in different essays or different pieces I navigate it differently. Sometimes, I feel like describing details and then sometimes I don’t. So I think it also has to do with how I’m feeling at the moment. And I think that there’s advantages and disadvantages to both. Sometimes I like, like in this essay, I was so young at the time and I think that I didn’t really know what was happening.

So in order to stay within the character to describe details, it wasn’t what I was thinking about at the time. So I felt like in order to stay. Stay in the time and place describing details wouldn’t have really fit the essay. So that was the reason that I didn’t use it. And most often I am a child when it’s happening, but then do I want to go back into my wise adult narrator voice?

And do I then want to fill it in or do I just want to leave it in the child’s voice? So that’s something that I also think about. And I think with each piece. It is different and it is a different choice. And I think that when I don’t give details, I somehow feel that the person who. I feel as if the perpetrator actually sometimes gains power.

Like if for some reason, like I’m stepping back and I, and I’m feeling shameful, for instance, then I feel that I’m giving power to the perpetrator. So then sometimes I want to force myself to give details because then it’s me. Owning my own story. And in that way, I feel that I’m taking back my power. But again, it really has to do with how I’m feeling and the audience and the essay itself.

Yeah.

No, I think those are really great points in terms of, you know, how do you navigate that material? Because you want to feel empowered by it. And yet you also want to do what’s required for the essay or the piece. And it, and it does, you know change. And what, what I liked is that you really.

Looked at a litmus test inside yourself. How am I feeling about writing this and not allowing shame to be the driver? I think that’s so empowering and important for all of us as I was reading the essay. And again, this is just me reading your essay, not, you know, it seemed like the most important piece was What was the narrator doing mentally to navigate this behavior from this boy and, and this relationship, which was clearly toxic because of who this person was.

That’s at least what I got. And as you were thinking about it, when you were writing this, You know, what decisions did you make, and where did you feel like you wanted the focal point to be?

Dr. Tamara MC: Yeah, I think while I’m writing, I don’t really have a focal point. I have something within me that needs to come out. And I don’t know that, and I think that that often happens in writing, that we get out our words, and then it’s through revision after revision, that we’re like, this is what the essay’s about.

I really had no idea. You know, often I don’t know what the essay is about at all, because I think the whole point for me in essay writing is finding out what I’m trying to say. And I think that’s the beauty of essay writing is learning. Like, like I go in with a question. I don’t go in with, this is what happened.

And these are the answers to my questions. I just go in, you know, this is still nagging at me. There’s something inside of me that needs to come out and I need to tell this story. And then through that. Somehow there becomes maybe this, I don’t know what, I don’t know if I’d call it this overarching question or sort of this theme.

I don’t really think of it that way because that feels, I feel too confined by that. But I just really wanted to explore this story with this person in my life and kind of explore the meaning of, of who was this person and, and what happened? Because I know that like, like stories of when I’m young, I don’t really understand, like, I like have these visions of things that happen, but I haven’t connected the dots.

And so I think that that’s what the essay does to me, but wait a second, this happened and this happened. Then I ended up here and then the story begins to make sense. It’s too mean.

Yeah, and what it sounds like, you know, I’ve talked about this with another writer recently is that, you know, the, the, what we want to go for is the, the questions living in our bones, you know, and those are the things that really nag at us.

And it seems like that was part of what was happening for you is that you had these questions nagging in your bones around what happened here? What is, what was going on with this boy? Why did it go like this? And, and so the essay writing process allowed you. To have that internal conversation around what was this and to begin to make sense of it But yeah, and I and I love what you just said is like when we’re actually doing the writing None of us have any idea what it is We just know like it’s important And it needs to come out and it is through the revision process that that whatever that central question is or that thing We really want to say comes to light.

So as you were writing this, what did you learn about this experience?

Dr. Tamara MC: So when I write about being a child bride, I was married when I was 12 years old. My father was part of a cult in Texas and I was married very, very young. And when I write about it, when I’ve workshopped my pieces, I’ve often been asked, but how did you like, Like, how did you like this person? Like, like I ended up loving this person who was my rapist, which I think I don’t, I mean, for me, it seems so easy.

Like, it wasn’t even a question. Like, how can you ask that? Of course I ended up loving him. Like it seems so obvious, but I think unless somebody’s kind of lived through that trauma and it’s kind of that repeated trauma of somebody raping a young girl. I don’t think that. Maybe people can understand like how a person can begin to like this person or to love this person.

So in this essay, I really ended up liking this person. Like, and that’s what I kind of tried to show, like through my diary, like I went from like, Completely horrified by this person to like saying, I love this person and I want to marry him. And that is like my very young, you know, 12, 13 year old brain.

But that’s, but I think that that’s something that I’m always trying to encompass are like, like all of these are true. It’s like, Like he was a horrible person, but also as a young girl, I really fell for him. Very, very complicated, I think, to describe. And it’s something that I’m still always working with.

So so yeah, I’m not sure what the question was anymore, but I’m not sure if I answered that.

Well, it sounds like you really discovered that it wasn’t just one thing, you know, that this, that this, that there were many layers to this experience. And that the many layers of this experience also speak to other things that are happening in your memoir.

It’s like, you know, one of the things I’ve talked with the students in this class and in other classes I teach is that, you know, essay writing can be a way of clarifying what you’re doing in a larger work. Because Through that, because it’s so short, you can get it done and finished. You learn something that can create an aha inside you.

Did you feel like you had that experience or, or did this feel like it was totally separate?

Dr. Tamara MC: Yes, I think so. But maybe kind of my aha was that, that I think for so many years, I felt so guilty about this experience. And I think that through writing it, it just seemed like Like, how could I ever feel guilty?

Like I completely had no consent within this situation. And that this part, like I thought there was something wrong with me the whole time. And I think in like putting the pieces together and realizing, wait, this person was very disturbed. So like they actually tried to kill their mother, like this person actually killed himself.

So for me to take all of the weight of this experience, Was like a whole lot of weight to hold on to, but then to kind of write through the essay to see that there’s absolutely nothing I could have done. Like this was a person that went like, like who was capable of murder and then was capable of suicide.

So. How could I take on all that weight? So I think that that was really, for me, that aha moment.

Is there, was it just like an evolutionary process or was there a certain point in the writing or the revising where you were like, Oh yeah, this isn’t mine.

Dr. Tamara MC: Probably evolutionary. But I think the one thing I knew. Was the beginning of the essay and the end of the essay, which I don’t usually know. Like usually I’m like, I don’t know where to begin. I don’t know where to end. Like this can go on forever, but this was an essay where there was such a clear ending that I knew the ending.

And so in that, I guess that in a way I knew what I was working towards. And I, and maybe that was what was like pulling me forward was like, I needed to get to the end to figure out how. Like Like, how was I connected with this person and how, like, like how were our lives intertwined? And I think that that’s, that was really super interesting for me is the idea that there’s so many people that come into our lives that we have no control over, like, this was just a child I was in class with in school.

He sat behind me, like, like, like in fourth grade. So there was absolutely no way I could have walked away. Like, there’s no way I could have said, I don’t want this boy in my life. Like only to a certain degree, but I found that super interesting, like how people just come into our lives and we don’t have control over it really, especially when we’re children and to kind of.

But then as a child, we think that we are so powerful and we could have controlled things and we could have walked away and I could have told a teacher or I could have told my mom, or I could have said, leave my house. Like there’s so many decisions that now as an adult, we think about, and like, if we do have children, like we would definitely tell our children to do those things, but then when our little bodies are in those situations, Like it’s impossible.

It’s just impossible in certain situations.

No, I think that’s really well said, and I love that, that aspect of it. And that’s one of the things that made me think about with like the experience I’d had was like, yeah, you don’t have control over those things. And, and, and yet you have to figure out what to do with them.

Right? And so as kids, there’s like a certain form of narcissism that we have. And this isn’t like, you know, the toxic narcissism we talk about with adults, but that we believe the world revolves around us and that, you know, we have power that we don’t necessarily have. So when things happen, we bring it back to ourselves.

Like I must have caused this, it must be my fault. I must have done something. And, and how, how hard that can be.

Dr. Tamara MC: Right. Right. Definitely. And I mean, just even like body image stuff, like that was something that I brought in, but. Here was this person who at such a young age told me that I had short arms and still to this day, I don’t wear sleeveless shirts.

And it’s like, how many years later, like almost 40 years later, but I’m still like ashamed of my arms from this one kid, like this one boy, Was just probably had a crush on me and was just trying to get my attention. But I took it so literally like, Oh my God, I have short arms, which I do have short arm. I mean, I’ve really, I mean, I’ve kind of concluded that I do, but still, it’s such a funny thing to like, to still hold on to and to like, still have to work through.

And

I loved in the essay how you’re able to navigate that. You’re like, oh no, how could I not have realized that I have Tyrannosaurus Rex arms? And the way you did that, you just created this really strong visual for us that, that emphasized the pain that the narrator was experiencing in that moment.

I mean, Whether you whether that was just how it naturally came out or that was through revision. It was

Dr. Tamara MC: brilliant. And I think that that’s that’s this moment that we all have where we go from innocence to knowing something and like how it just happens in like a time like something tiny can happen but it changes our whole world.

Like we see things in a completely different way. I hadn’t even Thought about my body until then. I had never once had a thought about my arms. My arms were just there. They fed me with my hands. Like they had no meaning to me. What’s whatsoever in my life. But after that one statement, they became like a focal point of my life.

Well, I want to respect your time. I just want to, if you’re comfortable with it, may I open this up to just a couple of questions from people in the class? Sure. Yeah.

Dr. Tamara MC: I’m here as long as you’d like me to be here. So, so

what would you all like to ask?

Speaker: I have a question about revision I first of all, you know, loved the whole, you know, piece and we’ve been talking about it. And just what that part where you said the innocence to knowing I love that.

That’s so powerful. But my question is, in revision, because I, my process is, throw it all on the page, I have no idea where I’m going, and then, now what? And so when you get to that now what, you know, how many revisions do you, I mean, do, could you guess that it would take for you to get to the piece that you do?

You published. Does that make sense? My question. No, it does. I’m trying to come up with an answer. And it’s okay. Cause it could take, you know, pieces of it. Right. Yeah. I don’t count my revisions. I don’t have like, you know, copy one copy, you know, I don’t have that. I just have my document and I work on it and I work on it and I change and I change and it’s over weeks and days and months, like I don’t have anything set.

But I feel like I always get to a point where I’m like still unhappy with the essay. Like I’m just unhappy and I know that it’s not ready. But then I also have, I also know within me because I just know, because I’ve done it a lot and just outside of essay writing, just within my own life, that there’s something inside of me that when it’s done, I know it’s done.

And I know that I’m going to get there, but there is no timeframe. There is no five revisions, 10. Two months, it could take six months, like each piece is so different that I think the piece tells you when it’s done, but not to rush the process, because there’s so much that goes on outside of the writing, like there’s so many pieces that we have to put together in our lives to be able to write that piece.

And so, So there is no timeline for that. It just takes as long as it takes, but just to trust that you’re going to know when it’s ready. But when it’s ready, it doesn’t mean it’s ready to be published. It means that it’s ready for you to maybe send it out to a publication and then to see what happens.

And then maybe you’ll get feedback or take it to a workshop or whatever it is. And so you’re still going to be getting feedback about it, that you’re still going to change. And so, so As soon as you think it’s ready, it’s really not ready. It still has like so many more revisions ahead, but that is just part of writing.

And I think like. So many years ago, I just loved writing first drafts because I love being creative. I love putting everything on the page. But now revision is just like, oh, it’s just so beautiful. It’s like that time where we just get to sit with these words and we just get to really Dig deep in. And when in life do we have that chance?

Like for me, it’s like this meditation. It’s like this healing that can only happen within writing. So it’s so far beyond the words on the page. It’s like within our soul, like our souls have to like change and heal in order for that piece to come into the world.

That is a great, great answer. And I love how it’s like, it’s in your body. Yeah. Thank you,

Dr. Tamara MC: I, I’m guessing. First of all, yes, please let me say this is such a powerful piece. What I admire so much is how much you say with so few words, how each word is just wham. And. I had highlighted, you got what you deserved, but now I realized based on what you were talking about earlier in your own meditation on this piece, that that is so powerful in terms of the narrator, the writer, the realization.

Wow. I just want to acknowledge that. Pang, based on what you were saying really hit me. My question has to do with chronology. You said that you, I loved also your point about you don’t go into it with a focal point or a theme or an anticipated meeting, but rather just what are the words that need to come out?

That’s, that just, wow.

Do

Dr. Tamara MC: you then just, in terms of your memoir as an example, you’re just writing what comes up? And What you know in your heart needs to be in your memoir. And then when that’s all down somewhere, you will then pull it together. Or is there another organizing principle you work with?

So on, I’m calling it the first draft because it’s like, there’s so many first drafts, there’s not just one, but on the first draft of my memoir, I was in Grub Street’s Memoir Incubator, which is a year long program. So I wrote the first draft during that year, and I ended up writing 400, 000 words, which is like the equivalent of four novels, like very long novels.

And so at that point, I just wrote the stories. I knew that I needed to tell. I did not know what the story was at that point. I just knew that these were stories I have, I had to tell, and I am so, so happy. Like, I have struggled for two years, like how am I gonna get down this memoir? So it’s not, I’ve had so much struggle, but I don’t think another time in my life I would’ve been able to capture these stories in the same way.

I just like went into, like I receded within myself. And went to that time period and was able to write from that time period. So I am so grateful that I have that on paper and now I don’t feel anxious. I’m like, like these stories are somewhere. I don’t know when or if I’ll ever need them, but they’re somewhere they’re out of my brain, which is so important.

Now I have to go back and I think about it all the time, like on my bike rides, whatever I’m doing, like, what is the story about that I’m telling? And now I’ve really honed in on what that memoir is. And now I’ve outlined it within my mind and I know what I’m going to get rid of. And I’m going to have to get rid of 320, 000 words.

Like that’s a lot of words. And it’s painful, but I’m past the pain now. Now I’m just excited that I know what the story is and I’m ready to really chisel it, like to take, like to take all of that and turn it in. To the book that I really want to write my first book So all of those words can go towards another book as well Like it’s not to say that they’re going to be lost they can go towards companion pieces They can go towards separate essays.

So nothing is lost and it’s also the exploration of becoming a writer being able to become a storyteller. And just like a painter, you don’t see so many of the paintings that they originally paint. That’s us as a writer. Like we’re doing all of that work that people aren’t supposed to see. Like that’s just for us.

So to go back to your I was also told this because I started, Kind of within my story going back and forth. And I had somebody say this to me and I keep this within myself. And I know that people have different opinions, but chronology is my friend. And. I like to think of it that way because I think when we get down a story, saying it chronologically is super important because it kind of keeps us on track.

It kind of creates this linearity that’s really important for us to process and kind of see what’s happening. How did we get from point A to point B? In the revision, then we can mix up the chronology, but we have it for ourselves. So it’s already there on paper. So that’s something that I think is really important in my writing is to write chronologically.

And it just keeps me so grounded. So you can start off chronologically and then you can experiment with structure later. So that’s, thank you. And then just lastly, this was a flash fiction piece, which means that it’s under a thousand words. And I am not a flash, flash fiction writer. Like I love, like I said, to write long, lengthy pieces.

So that was really hard for me to do because in so many places, I wanted to give so many more details. And I felt that it was really like kind of stark in a way. And the piece was stark. But I think for flash fiction, maybe I’m wrong, but maybe there does have to be a certain level of starkness because so much has to be left out.

So much has to be

left out.

Dr. Tamara MC: Wow. Thank you so much. That’s really inspiring.

Yeah. And I think that is the challenge and the grace of, of flash fiction is that, you know, you have to leave a lot for the reader to work out on their own. You know, you have to make the reader do a lot of the work. But I think you did that so well.

And there were so many we talked about you know, going cold. I don’t know if you ever read the brevity essay. If you haven’t, I’ll send it to you. And it’s really about how when you go cold on the page and going stark is one way to do that. You allow the reader to take on the emotions of the piece, versus, or you, versus the writer having them all on the page.

And so, we as readers were able to feel for this narrator and her experience and bring something to it that was a real gift. And I, I loved that that was, you know, something that happened in this piece. Though, I, I’m also like, Flash is not always something I do either. It’s very hard. The shorter it is, the harder it is.

It’s always true. And I also love what you said about linearity. I tell everyone, when you’re writing your first draft, write it as it, write it linearly. If for no other reason, then you will remember where everything belongs. But yeah, this idea of telling yourself the story first is so, so important.

Dr. Tamara MC: And just in terms of publication, I sent this to Brevity, which of course, who doesn’t want to be published in Brevity? Are you all familiar with it? But it’s creative non fiction flash, flash non fiction. So I sent it to them. I received a very nice response, but they did not accept it. And I was sad, but then I sent it to Dorothy Parker’s ashes and then it was accepted immediately.

So it really does like I mean, yeah, that’s just part of it. It’s like somebody may not accept it, then somebody else will accept it. And just this past week, after probably trying Brevity for over a year, I had my first piece published in Brevity. So it all like, it’s like, I don’t know, it’s so much work, but it happens.

But it’s just this tenacity and just not giving up. It’s like, it’s not maybe this piece, but maybe another piece. And I think the one way is just to read the publication so much and just to really learn the editors to like I know so many editors at this point in my career. And I read their pieces I read the publications I read the writers, and I think that that’s what really helps with publication, it’s not really.

our writing, but it’s like how we really know what’s out there and how are we within the writing and how do I know where to send my pieces because now I kind of know oh this piece sounds exactly like this publication and now I know to send it there and often the chances of me getting published there are super high now because I really learned brevity that I was able to finally get into brevity.

At first it was just like oh my goodness I love brevity but I didn’t really know brevity. So, so that’s the difference.

No, I think that’s a really great point. And that’s one of the things we were looking at because we compared your piece to another piece by Andrea Firth. And we were looking at what are the aesthetics?

How does this ending work? You know, are they ending on a, on a, you know, finished note or is there something unresolved? You know, how, what’s the flow like? And, and I totally agree. I think if you really want to get published in a reading many different pieces in that, in that publication is one of the ways that you can increase your chances.

But also what I love that you said is like, you’re not necessarily, when you start off with the first draft going like, Oh, I’m going to write for Brevity or wherever. I mean, sometimes we do have that, but that you allow this, the essay to be what it is. And then you think, Oh, this sounds like this particular publication or that publication.

So there’s a level of flexibility within that.

Corinne.

Dr. Tamara MC: Well, first what a beautifully crafted and powerful essay. So thank you so much for putting it out there. And in the context of it being hard for you to whittle it down. That makes it even just more amazing to me. So thank you for sharing that aspect. My question is about the types of responses you get to writing about trauma, either after publication or within like getting feedback from writing partners anywhere else you might receive input.