Want to listen to the article? Great--listen here!

Tamara MC, former cult member, interviews Christina Ward about Holy Food: How Cults, Commune, and Religious Movements Influenced What We Eat, An American History

I grew up in a Sufi cult in Texas during the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Our diets were completely restricted. For years we were strict macrobiotics. We were vegetarians, vegans, you name it—anything that restricted our food and protein intake. Food and water were deprived through fasting or any means available. Eventually we were told, we could survive by breathing alone. To become a breatharian was a goal for the children, not the adults, of the community. We had a strict hierarchal system in our cult. Leaders and their families were at the top. Then men. Then women. Then boys. And lastly, girls, like me. Girls’ food was the most restricted.

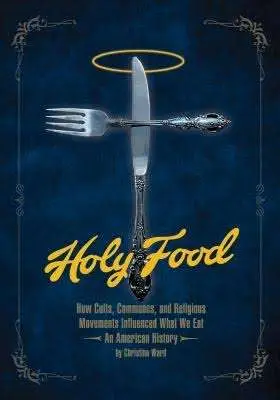

When I learned of Christina Ward’s new book, Holy Food: How Cults, Communes, and Religious Movements Influenced What We Eat, An American History, I knew I had to interview her. I initially received Holy Food as a PDF, and later received it as a paperback, which was a complete treat. The cover is amazing, a deep vintage blue, with a knife surrounded by a halo. The book, written in small print, is heavy and packed with more food history than you can imagine.

Ward spent seven years relentlessly working on covering the influences of preachers, gurus, and cult leaders on American cuisine. Some of the communities she covers are more well-known communities such as the Amana Colony, Seventh-Day Adventists, Hare Krishna, Rajneesh, and Nation of Islam, and then there are many obscure ones I’ve never heard of.

Ward poses the question, “Does God have a recipe?” Holy Food features 75 recipes from communal and religious groups, such as The Source Family’s secret salad dressing and Mother F*cker Beans, along with 100 historic black and white photos. Each has been tested and updated. In our Zoom interview, I asked Ward questions about whether she grew up in a cult and how she got involved with the project. We also spoke about her being a Master Food Preserver in Wisconsin and some of the cookbooks she owns that prepared her for her research.

I am in awe of the breadth and depth of Ward’s researching, and I highly recommend her book for anyone interested in cults, faith, food, and hidden American history, which might be all of us.

Tamara MC: I’d love to learn more about you and how you became interested in your book.

Christina Ward: Sure. So, I run Feral House publishing. We’re an independent publisher and have been for a long time, and I’m one of those “punk rock saves lives” kind of people. I went to school a little bit studying history, and that’s my obsession — food history. But I’m also a weirdo and have just been fascinated by that intersection of why people think that their God should tell them what to eat. Even as a little kid, I’d question why Catholic kids give up candy for Lent. When you go by a Jewish friend’s house, why don’t they get Italian sausage on their pizza? Those little things grew out of this lifelong curiosity about everything.

TM: I’d like to learn more about Feral House.

CW: Feral House was started in 1989 by Adam Parfrey. We do nonfiction with a focus on pop culture, memoir to some extent, and some occult, woo stuff. We use terms micro-histories and high weirdness. Many people will know movies made from our books more than the books themselves. A few years ago, there was Lords of Chaos about the early 1990s scene of Swedish death metal. Rory Culkin starred in it. Tim Burton’s Ed Wood. Those are both based on our books.

TM: I wasn’t even aware of you all existing. That’s totally up my alley.

CW: We’ve grown, and we morphed over the years. When you’re doing something for nearly 40 years, and when our founder, who had a big personality, died relatively young and unexpectedly in May of 2018, things change. Myself and his sister Jessica, who was always behind the scenes running things, keep it going. The books since 2018 reflects more of our interests than Adam’s.

TM: Where are you located? And where is the publishing house located?

CW: Feral House started in Los Angeles, then Adam moved to Port Townsend, Washington. I am in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and through the beauty of the Internet, I can work remotely. Being in the central US has been fantastic versus being in Port Townsend. I don’t know if you’ve ever been up that’s on the Olympic Peninsula, it beautiful but it’s very hard to get to and get from.

TM: I didn’t expect that answer.

CW: I know, because people think about publishing and think of New York.

TM: Is Feral House publishing your book?

CW: We have an imprint called Process Media. We also do a Self-Reliance series that we publish through Process. It would be foolish for me to take it somewhere else. I’ve had a few people comment, well, that’s easy. You don’t have to work very hard. And I’m like, you’ve never worked in publishing because whatever kindness your colleagues show to authors not in the company, they don’t show to you. So, it’s a much more brutal process. Because no one has a filter amongst ourselves, there’s no compunction to be gentle, it’s more like, “what the hell are you doing? This doesn’t make any sense.”

TM: It makes the book even better because I find that the more questions I get about my work, the deeper I get into it. It helps me think of things I hadn’t thought of before.

CW: Absolutely. People need to be more rigorous in interrogating themselves about their writing. And so sometimes, a little tough love makes a book better.

TM: Do you have any experience being in a cult or coercive community?

CW: I don’t. And that’s why it’s one of my fascinations. I’m 54, and I grew up in Milwaukee. Later, I learned about friends who grew up in coercive communities. When you use Dr. Steven Hassan’s BITE Model of Authoritarian Control, you figure out there are varying degrees of control. It was fascinating that my friends’ experiences were so very different than mine.

TM: What’s your background in food history?

CW: It’s just mostly coming out of interest. I’m also the Master Food Preserver for Wisconsin. I grew up in the city and was sent to my grandparents’ very primitive farm in the summers. I learned how to do oldy-worldy farm stuff, so that’s where the food history comes from. Then pursuing that interest to get my certification as a Master Food Preserver.

TM: I didn’t even know there was a title “Master Food Preserver.”

CW: People are more familiar with what they call Master Gardener. These programs were born from the great land grant universities in the 1840s. This idea is that if it’s a public university, and it needs to serve the public, and how you serve the public is by taking the research and science developed at the university and giving it back to the people, and that came through the Master programs. It used to be every county had a Master Gardener and a Master Food Preserver, so they were able to disseminate and help farmers and communities with questions. I even remember my grandparents’ farm mailing soil samples to the university’s extension office, and they would analyze it.

So, it’s this very old American idea, but sadly, with a lot of the budget cuts to most big state universities, these programs are being cut. I’m the Master Food Preserver for Wisconsin because they’re not even certifying people anymore. They stopped certifying people post-Scott Walker, so by 2013, they eliminated all the funding for these programs in Wisconsin, at least.

TM: So, they don’t even have a Master Gardener anymore?

CW: We have some Master Gardeners because it’s a less rigorous program. It requires less of an education. The Master Gardener programs have been watered down. They teach you the plant stuff, and you can go and help your community. Whereas with the Master Food Preserver, if you cook badly, you can make someone sick. If you can badly, you’ll kill someone. So, it’s a much more rigorous science-based process. You must understand it, want to be able to teach it, and then be able to help people troubleshoot.

TM: Can you tell me about your process? How did you begin this book, and how did it get into the world?

CW: I love cookbooks, and I collect them. I have for a long time. It was one of those weird light bulb things of always being interested in food history and cookbooks and then realizing about seven or eight years ago that I had a few cookbooks cults had published. Cookbooks were a revenue source for them in the 60s and 70s and an attractant to help recruit members.

I started researching more. I went down that pathway of figuring out that these cookbooks have had an outsized influence on American food culture. Then you start peeling that back to the early 19th century or earlier and then into the late 1800s, and you realize that this is a model that a lot of the new religious groups in the United States have been following. Part of what they believed is that you must either eat this or not eat that and here’s our cookbook to help you adhere to our very restrictive diet. For the Seventh Day Adventists and Rosicrucians, it was a common thing.

TM: How did you find the people for your interviews? Can you speak about your process?

CW: A lot of it was pulling threads. You start the research and then find out who to talk to. I always approach people where they want to be met. Some people are more comfortable in an email. Some people wanted to talk on the phone, and they didn’t want to talk on Zoom. You come in well-armed with information and just let people talk. One of the things that was helpful was just listening. Pausing is key—and being calm and patient and trusting. Don’t worry about what you’re trying to find out. It’ll all be revealed.

TM: What are some cookbooks you have?

CW: I mentioned the Rosicrucian cookbooks. The Mormons, the LDS, they publish a lot of cookbooks. I have some antique ones—the Amana in Iowa, a very fundamentalist German cult. And then, there are just bizarre ones. The Heaven’s Gate group published a cookbook. The Cosmic Cookery is a really good cookbook. They were a UFO group out of California.

TM: I’m familiar with some of the cookbooks you mentioned. I’d love to know why you think these groups restricted diets. What was the purpose?

CW: It’s a twofold purpose. The worst example is thinking about that BITE model. Anytime you can control a bodily function, you take away autonomy. You have control over people. And many of them did that infamously, and I write about Yogi Bhajan with 3HO that came to light about ten years ago. They were very yoga-centric, but then he was sexually abusing followers, as well as some very financial chicanery.

To join Yogi Bhajan’s group, you had to do the garlic fast for seven days, three times a day, which included eating a clove and drinking water. That was it. And so, if you could successfully do that, he’d allow you to take your next initiative step. The reason he did it was to separate people who weren’t willing to do it. His phrase was that he was separating Yogis from bogeys. So again, it was a kind of pressure testing.

Was someone going to be influenced? Was somebody going to be susceptible to following his orders? It’s about control, total control.

The other aspect of it is true believer groups have this religious influence. So, they are interpreting their holy scripture in some way to have significance with food, and that’s where you see a lot of vegetarianism and veganism. A lot of the groups that are Hindu-inspired subscribe to this idea you can’t harm any living thing, so you’re not going to eat meat.

Many Christian-influenced groups go back to what’s called the Edenic Covenant. And that’s always funny because it gets interpreted in such different ways that either God gave us dominion over the entire earth and we can eat it all and do whatever we want with it. Or we are the caretakers and protectors of the earth, and therefore, we are responsible and should not eat everything. There are groups that have two different interpretations. And that’s a common thing in all these cults and new religious movements is that it’s all interpretive. They’re all cherry-picking and taking little bits and ascribing a lot of meaning, and then they give meaning to food.

The third pathway with true believers goes back to the cash route, to the Leviticus, to the Jewish food rules. There’s a fair number of modern groups that are Christian, but they’re essentially Anglo Israelite. They believe that they’re the true tribes of Israel and the Jews are the bad guys. They follow a very traditional Jewish diet.

TM: I was thinking about garlic. I wonder if the garlic had something to do with isolation, too, which is so much part of cults. I wonder if people were consuming so much garlic that others wouldn’t even want to be around them, so it was a natural deterrent and isolation tactic.

CW: In my research and with the people I spoke to, no one talked about that. It was pressure-testing to ascertain whether someone would follow these restrictive ridiculous rules. Bhajan himself is very funny. He came from India, and his background is both Jain and Sikh, but he rejected a lot of the traditional Jain and Sikh food rules when he came to the US.

He just did whatever he wanted and imposed his tastes on a lot of people. They had a restaurant for a while, too, and a lot of the food is what we think of as Indian-inspired, but it’s not what is traditionally Indian. A lot of Indian cooking doesn’t use garlic because of the belief that it’s too strong and offensive to the gods or to certain deities.

TM: I find it interesting garlic was chosen of all things.

CW: Nobody had a good answer for it. And there’s nothing in the writing. I mean, isolation possibly. A lot of times, traditional monastery cooking could be very transgressive in their restrictions and protocols.

TM: What do you think about vegetarianism and veganism?

CW: It comes from the notions of ahimsa, rooted in Hinduism and Jainism. If you’re going back to the original idea in India, there’s no meat but a lot of dairy. So, it becomes twisted when it comes to America and vegans don’t consume dairy. A psychological asceticism comes through the idea that: “I’m pure because I’m restricting my diet. I’m only eating plants and things natural to the earth. I’m peaceful because I’m not sacrificing any animal to sustain myself.”

In the modern interpretation, you see a lot of veganism and vegetarianism in a practical sense. Mid-century through the ’60s and ’70s, meat as a protein was very expensive. A lot of these groups relied on cheap proteins like beans and lentils. It was almost a forced vegetarianism due to the economy. Whereas the leaders probably were eating steaks, the followers were being fed a very minimalistic diet.

TM: What do you think about the keto trend? It seems like it was so cool to be vegetarian, and now it’s not. We’ve gone in the opposite direction.

CW: That’s very funny because it’s also related to this kind of alt-right, Neopaganism type of religions It became “keto, hey, it’s great. You’re going to lose weight. This is a better way of eating.” And now it’s morphing into the all-carnivore diet, or the raw meat diet, which is insane. And then it takes on the religious trappings. What this comes down to is the human essence of tribalism. To have separation and identification. America, as a society, has become disjointed.

We don’t have the same set of social structures we once did. As a society, people then seek to form new communities. How am I going to find someone that I’m going to bond with? Well, I’m going to bond with carnivores. I’m going to be keto. It becomes its own kind of cult. It becomes a bonding mechanism as well.

TM: Why do a lot of cults have restaurants?

CW: It’s all very fascinating. The reason the United States has so many of these cults and new religious movements is trifold. One, because of immigration. We have so many influences coming in. Secondly, the First Amendment. No other country has this kind of establishment clause that allows for this freewheeling idea of religion and prevents the government from doing anything about it. If you’re in Europe, they still have nominal state religions. You go to the UK, it’s the Church of England. If you look at Germany, there have been lawsuits by the German government to prevent Scientologists from establishing groups and headquarters in Germany. But the US, of course, doesn’t have any of that.

The other thing we get into the restaurant is the tax code. The tax code changed in the early 1900s and established something called nonprofits. Before that, churches were just churches. Now, as a legal entity, there’s absolutely zero reporting required for churches, and it allows them to have revenue as long as it’s supporting the mission. So that’s the wiggly part. That’s why a lot of these restaurants support the mission. But really, it’s a revenue stream, and what a great revenue stream because if your followers are all working in the restaurant as part of the mission, you don’t have to pay them. That’s a much higher profit margin than a restaurant with paid employees.

TM: And what about free labor? You just touched on it. What did you learn?

CW: Everybody gets assigned a job in the cult. Some people work in the restaurants. It depends on the nature of the specific group. Some of it’s worse and more coercive than others, but it’s always long hours, no pay, and grueling work. If you look at the Yellow Deli, they’re primarily on the East coast. They started in Chattanooga, Tennessee. They’re one of those Anglo-Israelite groups, very fundamentalist Christian, and very coercive. They’ve been brought up on charges in Vermont on child abuse. They’re forcing young kids to work in the restaurants. And so that’s a terrible, extreme example. There’s no choice. This is what you do.

And then conversely, looking at the United House of Prayer For All People, they have cafeterias affiliated with the church where they serve lunches, and early dinner; traditionally soul food. Mostly women are doing the cooking. They volunteer for a shorter period of time, around three to six months. It’s considered a great service to the church itself. So that’s a few examples of how people are used. That’s one of the ways that the government has been able to take down some of the worst cults is by charging them for violating labor laws.

TM: In terms of food restriction, there are also weight restrictions, especially on women in cults. Do you think that there’s anything that has to do with these diets that also keep women skinny?

CW: It’s all about control. An American disease, cultural disease, forced on women. And so, depending on the culture, there was food restriction, with a goal towards thinness many times. Though it was also about decreasing protein because if you keep protein levels low for a long time, women stop menstruating, and they don’t get pregnant. Depending on the group’s goals and beliefs, some groups did not want a lot of babies around. Others did. Also, if you don’t have a lot of protein, you lose energy. You don’t have as much energy to rebel or start thinking for yourself if you’re hungry all the time. Of course, there were specific groups that were focused solely on weight. Gwen Shamblin built her billion-dollar empire by teaching women how to restrict their diets and lose weight.

TM: What did you learn from your project? Where are you now?

CW: I’ve always been an atheist, and so I didn’t come away with any newfound revelation. I didn’t find God in the food, that’s for sure. But what I did find was the interconnectivity and how, especially in the United States, all these groups are super connected, whether by this guy knew this guy and studied with him or the thread lines of belief. I hope people take away that there are so many ways to believe what you want to believe. The problem comes when you try to force someone to believe what you believe and do what you’re doing based on your belief. That’s my big takeaway. Your God can tell you what to eat, but he can’t tell me what to eat.

TM: I love that. And what is your diet? How do you eat?

CW: I was severely ill about five years ago with a tick-borne disease. Because of that, I have Alpha-gal syndrome, which is a meat protein allergy. So, I’m a vegetarian by force.

TM: What are some of the things you keep in your fridge and cupboard?

CW: A lot of vegetable stuff, of course. For food preservation, I have a sweet tooth, so, I like making apple pie filling and doing other pie fill things with fruit because then you just put the jar in the pot, and you’re good. A lot of jams, jellies, chutneys, and pickles. It was just cucumber season here, and we had three giant two-gallon jars of crock pickles. When I’m talking about canning, I always say you should only can what you’re going to eat. Otherwise, it’s just wasteful.

Dr. Tamara MC is a cult, child marriage, and human trafficking Lived Experience Expert who advocates for girls and women to live free from gender-based violence worldwide. Her Ph.D. is in Applied Linguistics, and she researches how language manipulates vulnerable populations. Tamara attended Columbia University for an MFA and has been honored with residencies/fellowships in Bread Loaf, Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Sewanee, Ragdale, Cave Canem, VONA, and VCCA. She’s published in prestigious outlets such as The New York Times, New York Magazine, Newsweek, Salon, The Independent, Food 52, Parents, and Thrillist. She’s revising her debut memoir, CHILD BRIDE: MARRIED AT 12 IN A SUFI CULT.

Link to original article