Want to listen to the article? Great--listen here!

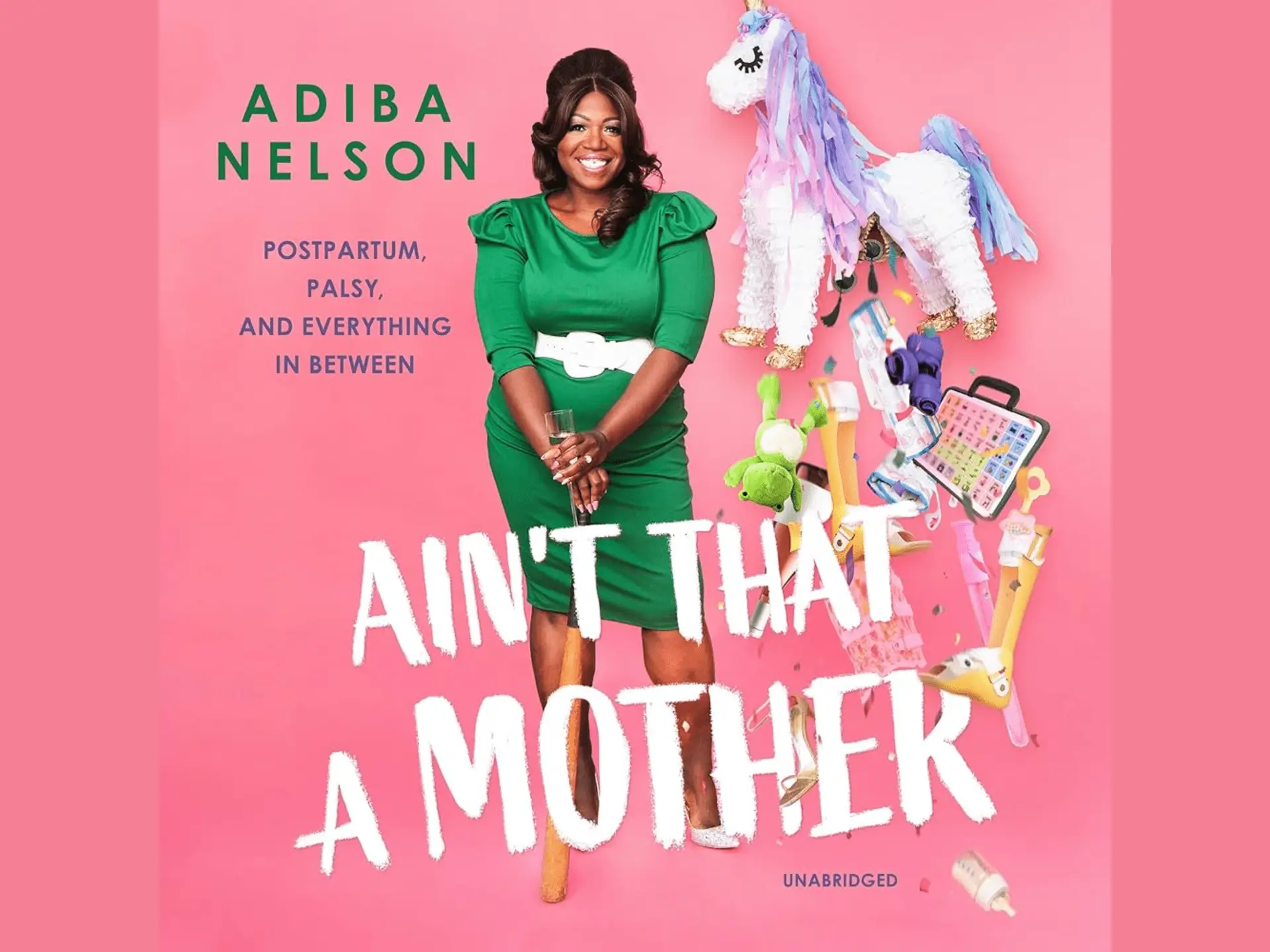

Purchase Adiba Nelson’s debut memoir, Ain’t That a Mother: Postpartum, Palsy, and Everything in Between, for the book jacket alone and clutch it under your arm like you would your prized handbag, using it as your statement accessory. The cover is gorgeous and girly—cotton-candy pink with a gold-horned unicorn piñata. People may stop and ask, “What are you reading?” Wink, wink, I’m speaking from experience. I was inhaling a salad, chomping on a jicama chunk, when a white man in his 80s staggered over to my table and asked that very question.

How can we miss Nelson on the cover, holding both a baseball bat and a glass of wine while wearing a shamrock green dress to match a Kermit-the-Frog-look-alike stuffy, with a smile that reaches to the sky? Nelson is on point, not only with her outfit and book cover but also in life, motherhood, and humor. Ain’t That a Mother is about traversing life’s challenges while God, a Higher Power, Jah, or whatever you call Him/Her/Them looks down and cackles. What makes a mother? There is no single definition in this comedic motherhood memoir.

The memoir covers many topics: disability, the differences between po and poor, strong Puerto Rican mothering, your ride-or-die gals, step-parenting, single motherhood, addiction, and the healing power of burlesque. Nelson’s writing matches her witty and larger-than-life personality, so be prepared to ugly laugh and perhaps also ugly cry.

Nelson’s dialogue is striking. Her anecdotes are so embodied, you feel like you’re in that time and place with her. She writes, “If having a baby was to be compared to running a race, it’s like hearing the shotgun, take off running, and then tripping and breaking your ankle ten steps in.” Spanish words are italicized but not defined, forcing readers to do a little extra work while also making a statement about the legitimacy and power of language, all languages. But also be prepared for some cursing. In an interview, Nelson compares curse words to exclamation points.

Nelson’s pregnancy with her only daughter begins with the singer Jill Scott. One of Scott’s songs is playing in the background while Nelson has unprotected sex with her boyfriend, Jeff, whom she met only a month before. Nelson writes,

Jill Scott owes me twelve years of back child support. I’m not kidding. If it wasn’t for Jill Scott and her irreverent, sweet melodic voice pouring out of the speakers on my bedroom radio that hot-ass August afternoon, I would have never gotten pregnant.

Nelson states that she isn’t prepared to be a mother, and certainly not with her brand-new boyfriend, so she opts for Plan B.

Many of us don’t know (I didn’t) that Plan B isn’t guaranteed for women over 155 pounds or 30% BMI. Nelson also has no idea and is surprised months later to learn she’s pregnant. She writes,

Plan B did not work. I shit you not. Those two tiny pills may as well have been tic tacs because no sooner than I had placed the cap on my pee stick and shook my hand free of my own urine, did that damn thing light up pink like a goddamn 1980s fanny pack. I was pregnant.

Now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, Nelson’s story is even more timely, since her memoir is about the necessity of women having choice over their bodies. It’s also a cautionary tale for others for whom Plan B may not work. Nelson writes,

Just… let’s pause because I can’t in good faith, and certainly not in the name of sweet Black Baby Jesus, go one step further without sharing some very pertinent information with you that surely would have come in handy had it been written in BIG-ASS, BOLD-ASS LETTERS ON THE GODDAMN BOX OF PLAN B ELEVEN YEARS AGO! Come close Y’all ready for this? Plan B doesn’t work if you weigh more than 155 pounds.

For the last four weeks of Nelson’s first trimester of pregnancy, her doctor puts her on bed rest. She doesn’t do much more than sit on a couch or lay in a bed. She’s miserable. Pregnancy may be beautiful for some, but Nelson, through describing her own difficult pregnancy, breaks the stereotype.

You know how most women go through pregnancy and they look like they’re about to enter a beauty pageant…? If Freddy Krueger was a pregnant woman, I was her. In addition to balding and burning, I was also apparently turning into a damn jungle cat because I broke out in cheetah-like spots all across my cheek and neck.

Nelson also becomes calcium deficient and loses a tooth.

After the birth of her daughter, Emory, Nelson is bogged down by postpartum depression. When does the fierce mothering mama float into the body of a mother? For Nelson, it isn’t at birth, but eight weeks later. Up until that point, Emory’s dad, Jeff, does the majority of caretaking because Nelson fears dropping her newborn. Then magically, one day after she works up the nerve to bathe Emory alone, the fog lifts. She writes, “What happened next will forever live in my memory as the exact moment the weight disappeared. I laid her on my bed, leaned over her, and made a silly face. She laughed.” Nelson continues making funny faces, and Emory continues to laugh and smile.

Nelson says this was the turning point and writes, “My child knew me, and for that moment, if only for that moment, she liked me.” From then on, she steps into fierce motherhood and becomes a bat-swinging mama (as her book cover suggests), willing to take anyone to bat that dares mess with Emory, her pride and joy. Nelson acknowledges that women’s experiences are very different and mothers should seek out help and not navigate this very scary time alone.

Early on, Emory begins missing milestones. Although Nelson brings this up at her checkups, the pediatrician refuses to listen. She is finally able to make an appointment with a specialist, who suggests an MRI. Almost a year after Emory’s birth, Nelson learns the official diagnosis: bilateral schizencephaly. This means Emory has two holes on both sides of her brain and will likely never walk and will need speech therapy for the rest of her life. Nelson’s forced to navigate a fractured healthcare system, but throughout it all, she remains her child’s number one advocate—her ride-or-die gal.

When Emory is ten, she’s diagnosed with an acute seizure disorder. I’ll likely not forget a visceral scene where Nelson administers Emory’s medicine by force through her daughter’s rectum. My heart broke, feeling sorrow for both Nelson and Emory, warriors in distinctive ways. Nelson’s anger, determination, and will are palpable. She saves Emory as her daughter’s eyes roll back, her lips turn blue, and she foams at the mouth.

Alongside Emory’s health issues, Jeff is battling his own. Nelson questions the limits of promising in sickness and in health. Does she stay with him and look after his health if he isn’t willing to look after himself? Eventually, this is where she parts ways with Jeff, wishing him well and knowing he’ll always be Emory’s dad, but she has to be whole and well to take care of herself and her daughter. This section had me thinking about the stigma of women as caretakers and what happens when we break from these roles and choose something else. Do we stay? Or go? Perhaps in Nelson sharing her truth, she gives us strength and permission to leave.

I started but stopped counting how many times Nelson calls Emory beautiful. At the memoir’s core is the notion of beauty and the many ways all of us are beautiful, even if not traditionally. Before Emory’s MRI, Nelson sings a song to calm her before anesthesia. She sings, “Who is the prettiest girl in the whole wide world? She makes my heart unfurl! Eeeeemory…” After Emory is out cold, the doctor asks her about the song, saying he’s heard it before. She grins and says, “It’s the theme song to Caillou. I just changed the words.”

When parents believe their children are beautiful, kids go into the world with a certain confidence. Their inner and outer beauty become unflappable, which seems to be the case with Emory, who knows she’s beautiful because her mama told her so.

Ain’t That a Mother is also a story of place: Puerto Rico, New York City, and Texas, communities with diverse populations. But when Nelson cannot afford her home in Texas, her mom convinces her to move back to Tucson, a town where less than 4% of the population is Black. Nelson wants her daughter to grow up with kids who look like her, which won’t be possible in Tucson. And what grown child wants to return home to live with her mother with a kid of her own in tow after living alone? Nelson surely doesn’t, but realizes it’s her best financial option as well as the greatest support system for her and Emory. Nelson returns to her mother in Tucson, but is Arizona—her hometown and mine—ready for her Black disabled daughter? This isn’t a question for Nelson. Instead, she issues a command and states that Tucson has no choice but to be ready.

If I haven’t convinced you to buy this memoir because of the flashy book jacket, the humor, the heartbreak, and the failures of the healthcare system, then let me try to lure you with footnotes. I’m an academic and used to bland footnotes that I often overlook, but in true Nelson fashion, she spruces up her footnotes, transforming them from dull citations into laugh-aloud moments. Footnotes address the reader and explain statistics, facts, and funny tidbits.

Footnote 24 reads: “Good Christian ladies, please don’t come for my neck, and please don’t stop reading here. (a) The good book says thou shall not judge; and (b) I am a human being describing my very human feelings and experiences. Allow me the grace to experience this with me.” In Footnote 26, she writes,

Reader, you can judge me if you want to. But what you’re getting here is the pure, unadulterated, unfiltered thoughts of a new mom who up until nine months prior to this moment had reconciled herself to be everyone’s cool Aunt ‘Diba. So yeah, I think a healthy dose of shock and awe are apropos for this moment. Continue.

Now, I dare you to buy the book for the footnotes alone—you won’t regret it.

Nelson’s memoir feels like it’s not written with an inside voice, but with an inside-the-soul voice, the authentic and vulnerable voice we all have but cover up because of shame and fear of judgment. Using self-revelations, she allows us to explore our darkest feelings. What do we need to burst out of our bodies, give birth to, and give voice to in order to survive and thrive?

Nelson exudes so much self-love and confidence that I stood taller and walked with more pep in my step after reading her memoir. My voice even became more confident. At the end of the book, Nelson gives tips on how she finds more self-love and compassion through therapy, journaling, and daily self-affirmations while drinking tea. Her affirmations include: “I am beautiful inside and out. I am a great mom who gives more than the bare minimum to my daughter. I boldly ask for the things I want, and assuredly decline the things I don’t.”

In Ain’t That a Mother, Nelson brings bling and badassness to motherhood. May we all add a little more sparkle and joy to our own mothering. May we become more fearless, more Nelsonesque.

Link to original article