Want to listen to the article? Great--listen here!

I’ve long felt shame that I knew much more about my Muslim heritage than my Jewish side, but this year, I’m diving in.

I don’t know how to read or write Hebrew. I haven’t memorized a single prayer. I am illiterate regarding Judaism, yet I’m Jewish — a truth I know with certainty.

How I interpret and process my deepest emotions comes from my relationship to Judaism. I am firmly planted in Judaism as I connect to the earth. How the world sees me through their eyes as someone they don’t recognize, always asking, “Where are you from? What are you?” is a piece of otherness inherent to Jews. My heart, skin and feet are Jewish.

Despite this, I can barely tell you the name or meaning of a single Jewish holiday.

When I was 5, my father converted from Judaism to Islam; he followed a Shaykh from Tucson to Texas and left my Jewish mom and me for a different religion. Four months of every year, I lived with him on a Sufi Shi’ate commune between Austin and San Antonio with 100 other members, five siblings, and a stepmother — all Muslims.

My father is a language prodigy and became fluent in Arabic soon after converting. He taught me Arabic from the time I was 6. I took after him in languages; I learned to read quickly. I memorized prayers speedily. I was intimately familiar with the Quran from an early age.

I also asked thousands of questions — most of them following under the umbrella of why and how. I needed to know the meaning behind Islam and Arabic. I quickly became the star Muslim child in the community — the one with the greatest curiosity and most in-depth knowledge and understanding.

I went on to get a bachelor’s degree in Middle Eastern studies. I lived in Egypt and studied at the Arabic Language Institute at the American University. I got a master’s and a Ph.D., becoming a scholar of Islam and Arabic. I know Muslim holidays through study, but most importantly, my posture during prayer remembers. My mouth remembers recitations.

Bubbe Mina, my maternal grandmother, grew up celebrating Jewish holidays in Lithuania. During my childhood, she spoke of rituals, prepping, her mother’s hands kneading children’s hair without running or hot water. Honey dripped from her lips, love and nostalgia oozing.

After surviving the Holocaust, Bubbe mostly stopped celebrating. She called herself an atheist, but I’m not entirely sure she didn’t believe in God. She often said she couldn’t understand how the Holocaust could happen and how her parents could be murdered with a God above. In her questioning, she might’ve lost attachment to a deity, but her devotion to Judaism remained fierce.

Above all else in the world, my bubbe identified as Jewish.

Even though my mother occasionally went to Hebrew school with her friends, my family rarely attended synagogue after I was born. Sometimes we’d attend a service, but primarily for free food. So, if anything, holidays were a time for Bubbe to stuff her pocketbook with herring, lox and brisket wrapped in white paper napkins, smelling up our blue Subaru as we drove home.

Bubbe cooked matzah ball soup, cheese blintzes and potato kugel, so I grew up knowing Judaism through her stories of the Holocaust and food. But here I am, a grown adult, researching Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur for the first time. Since my bubbe died 11 years ago, my knowledge of these holidays won’t be through tradition or education, but rather through Wikipedia.

Unlike Islam, I am no scholar of Judaism. I wish I knew more. I wish I had more traditions and more Jewish family and friends, but I don’t. I am in the middle somewhere, where although I feel part of both religions, I often feel left out, alone within myself.

I feel guilty, ashamed, like a traitor, for all I don’t know, what I think I should know. But I am also deeply curious.

This year, I’ll likely be alone on both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. I won’t be sharing a meal with anyone, but I will be creating new rituals for myself. I will use the holidays as a time for reflection, review and reassessment. And like I’ve been doing my whole life, I will ask many questions.

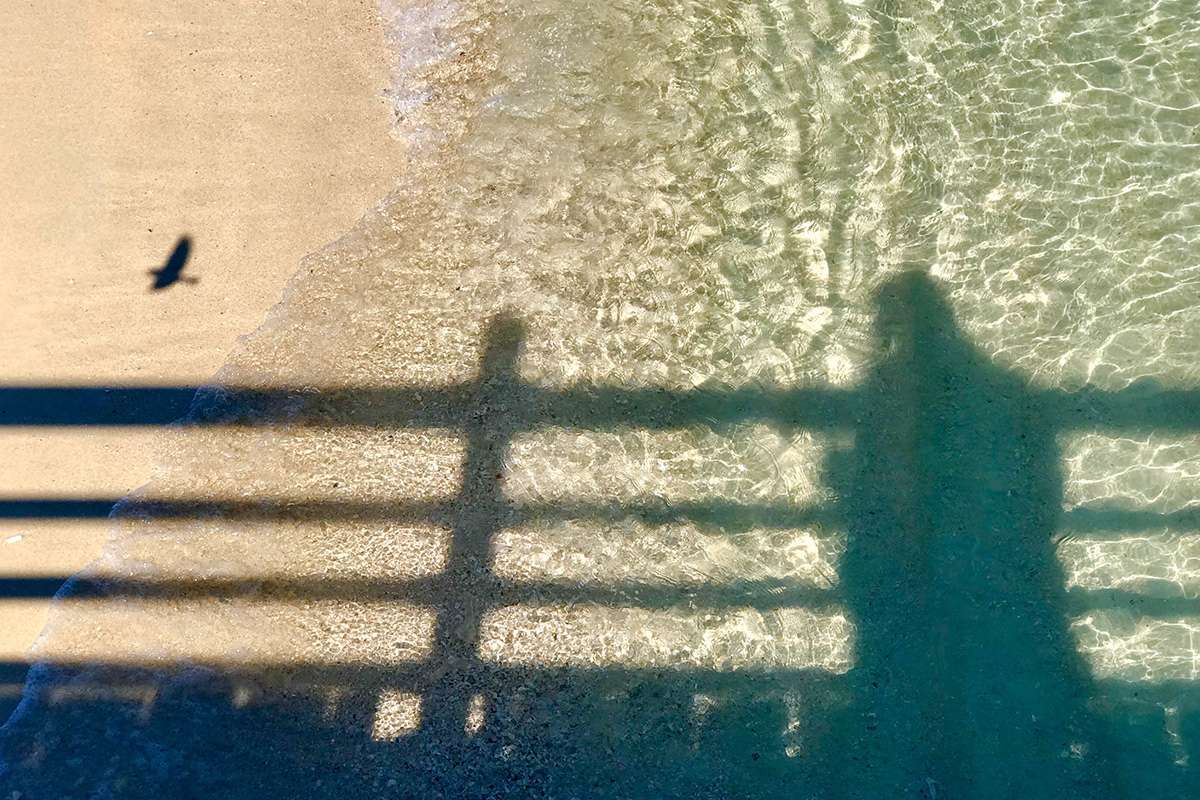

What do I choose to leave behind from the previous year? What unhealthy bonds or patterns do I wish to break? What can I cast into a river, sea or lake, even if metaphorically, to make space for what excitedly waits to populate my life? What do I choose to keep and expand? How can I create more connection, more community, more support for others and myself?

How can I generate more joy?

This year, I leave behind shame, the feeling of not being enough because I don’t know enough, and next year, I hope to bring forth more kindness towards and forgiveness of myself.

Identity is complex, complicated and layered, and I will always remain both Jewish and Muslim. I love both people, religions and traditions, and although I’m more knowledgeable about Islam, my Jewish self and identity are constant, unbreakable and defiant.

I plan to enter the Days of Awe with honey-drenched lips, filled with gratitude for having one more day, one more year of life.

Dr. Tamara MC

Dr. Tamara MC (she/her) is an applied linguist and researches language, culture and identity in the Middle East and beyond, focusing on women. She also attended Columbia University where she worked on an MFA in both poetry and creative nonfiction. She is currently seeking representation for her debut memoir which chronicles her life growing up simultaneously Jewish and Muslim on a Sufi commune in Texas.

Link to original article